Do well-indexed very large heaps have practical use cases that are not found in well-indexed very large clustered tables?

Of course. Clustered tables have many advantages, but they're not always the optimal solution. Note though that some SQL Server features require a clustered index or primary key.

A clustered b-tree index largely materialised in the logical ordering of its leaf level pages does provide some benefits 'for free', but there are also disadvantages:

You can only have one such index, since it is the primary storage object.

The upper levels of the b-tree can represent an overhead as mentioned in the question's linked article.

The extra I/O effect is real, though often overstated. The upper levels do have a tendency to remain in cache, but this is not guaranteed. In any event, the extra pages must be latched and navigated for each lookup.

The clustered index includes all in-row columns and off-row pointers at the leaf. This makes the space between leaf index keys maximally large. In other words, the clustered index is usually the least dense index.

The same table organised as a heap would require a nonclustered index to provide a similar access method. The upper levels of that nonclustered index will be very similar to the clustered case, but the leaf level pages will be much denser, in general.

Most very large OLTP tables require multiple indexes to support a good range of queries. These nonclustered indexes will normally be narrow, preferring highly selective index searches with a small number of bookmark lookups over wider, covering indexes. Fully covering indexes are often not practical in this scenario.

Each of these access paths benefits from the higher leaf density and/or direct access provided by the RID row locator, rather than indirection via the clustering key(s) and the associated b-tree.

There was a time when single-column integer clustered keys were (too) common, making the 8-byte RID twice as large. This is much less the case these days, as even so-called 'surrogates' are usually bigint. Many clustered indexes are of a wider type, string-based, or multi-column. The size of an RID is more often an advantage now.

Replacing a very large clustered table with a heap and single nonclustered index will not generally produce benefits. The advantage, if any, comes from an increasing number of optimal nonclustered indexes needed to support the workload with acceptable performance. Each nonclustered access method benefits from the more efficient lookup path.

In the limited scenario described in the question, the heap arrangement is worth investigating if there are many highly selective OLTP queries that would be best served by a medium to large number of highly optimized, narrow nonclustered indexes with selective RID lookups as well as index-only range scans.

How much benefit you see depends on the performance characteristics of the hardware, and the fine details of execution plans selected by the optimizer (prefetching in particular).

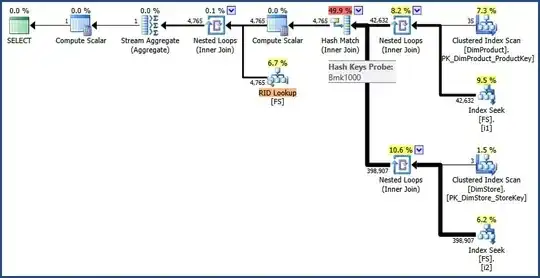

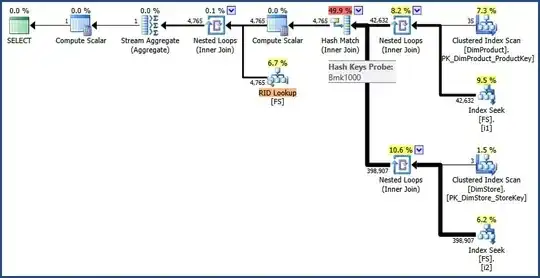

Depending on other tables in your workload, the large heap with secondary indexes may benefit the built-in star join optimizations. These plans often feature base table lookups (fetches).

All that said, none of this is new. It's fairly rare that this aspect of performance would trump all other considerations. Nevertheless, it is a genuine factor that can be important to consider. Most people will end up perfectly happy with a clustered scheme, even if slightly better performance is technically achievable with a heap base.

Downsides

All the usual caveats with heaps still apply. Be aware of space management issues and how widening updates can result in forwarded records.

In particular, though the more direct lookups can benefit read performance, single row insert performance may be much worse. This is because heaps do not maintain a fixed insertion point for new rows—the new row will be added wherever there is free space.

This requires a free space scan, in IAM-order, using PFS pages to locate an existing page with sufficient free space available. For an extremely large heap with little or no existing free space, this scan can add very significant overhead.

Metadata caching means subsequent row insertions in the same statement do not pay the full price. A single row insert into a huge full heap is the worst-case scenario. Remember that heap tables can also be partitioned, which can mitigate this concern if each partition is kept to a reasonable size.