Shouldn't the exit from high-priority task be done by returning back

to the ISR and then returning back to the low-priority task?

A lot depends on the exact details of the O/S design. But assuming the diagram is accurate for the case under discussion, then interrupts by definition are more important than the highest priority task (or process, or thread -- each of which are distinct but not necessarily distinct in exactly the same way in all operating systems -- I'll just use 'task' in the rest below.) That's the answer to your second question. But I'll get to that, shortly.

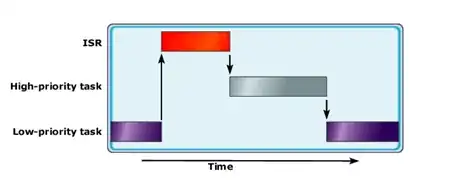

So the interrupt takes place, the O/S preempts the task and saves important state in a task state structure (used to restore the task's state before re-starting it later), and then the interrupt handler executes for a time. Let's say that in doing so it places some data into a network receive buffer and that a higher priority task has been waiting for a network receive buffer to become available.

For the interrupt routine to truly complete, it "signals" any tasks that have been waiting on a network receive buffer. (It calls a function for that purpose.) The function it calls finds that there is, in fact, a task waiting on it. The task had previously been moved OFF of the ready queue and onto the semaphore queue, while waiting. However, now this function moves the task from the semaphore queue and back onto the ready queue. It does this by calling an "insert" function designed to do that job. The insert function now inserts the high priority task back into the ready queue. But, of course, it does so with the higher priority in mind. And this makes it the "next task to run."

Now, the interrupt exits. But in doing so, the O/S now restores the state of the top (highest priority) task that exists in its ready queue. This NOW, it turns out, happens to be that higher-priority task (which was just moved to the ready queue.) The task state that the O/S restores next, is the task state from this highest priority task. And so it is re-started now, with the prior task still sitting around in the ready queue, waiting.

Most operating systems will work like that. So it's not hypothetical, it's very practical. But one could ALSO design an operating system to behave differently, too. It's just that it is actually very easy to do it the way I just described and most users of such operating systems want and expect that behavior. Since it is expected, natural, and also easy to do, it is usually the way it is done.

That is... if preemption is supported. Some embedded systems make that rather difficult -- particularly when non-preemptive, proprietary libraries are being used and there is no possible way to actually save the preempted state, correctly, since there is no access to the internals of the library state (due to lack of source code to read and/or tie into) and therefore no possible way to be sure you can return to the task safely. In cases like this, one might consider a voluntary release of control through a "switch()" call executed periodically by each task. Or by tapping into the compiler's generation of function call prologues and epilogues and inserting a special call at those points (since it is usually safe to switch between completed calls.)

How is the lowest-priority interrupt in a system more important than

its highest-priority task?

If we are talking about hardware interrupts (software generated ones are a different matter, perhaps), then it is usually the case that there is a very limited time to respond before a hardware buffer is over-written (for receive) and/or that sending out information is very important be kept in a relatively continuous form.

For example, suppose the device is taking in measurements from an ADC, doing some processing on those values, and then sending out a measurement on a regular basis to a DAC. (Let's say that this is a temperature measurement that may be used as part of a closed loop control system of a FAB making ICs.) It may be VERY IMPORTANT that the ADC is read on a very repeatable timing cycle and that the DAC is also updated on a very repeatable timing cycle and that the delay between the ADC input and the DAC output must ALSO be highly precise and invariant. (For example, a fourier transform might be performed on the values read from the DAC output by the next device in the chain or else a closed loop control algorithm's design may depend upon accurate estimates of the time delay as well as the measurement frequency.)

In cases like the above, it's vital that the interrupt events be serviced well above the priority of some task with unknown duration.

That said, one could just as easily suggest cases where it's not as important. For example, a user-pressed key might either generate an interrupt or also be polled. It could easily be the case that even if an interrupt is permitted (and polling isn't used), that the priority of responding to that key press event should be lower than some tasks that are running. But then, it's usually better to just poll it, instead. There would be no good reason to let a key-press event generate interrupts in that case, so I think polling would be selected. And that gets us back to the remaining interrupts, which again are probably important.

So, in general, you design things such that interrupting events actually are more important than all of your tasks. You would generally NOT design things such that some interrupting events are less important. You'd poll those, instead.