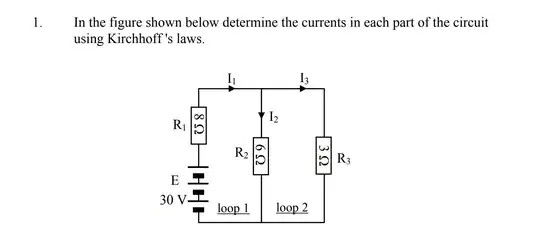

Your equations look correct to me. Congratulations on keeping resistor voltage polarities consistent with current direction labels, that's usually where people mess up. Your question, though, is not an electrical question, it's a maths question.

You have three unknowns, \$I_1\$, \$I_2\$ and \$I_3\$, and three independent equations relating them, which means they have a solution.

You may use any technique you choose for finding \$I_1\$, \$I_2\$ and \$I_3\$, including matrix manipulation, and including variable substitution. They will all yield the same results, since the underlying algebraic principles of these techniques are fundamentally identical.

I suggest you try both approaches, and prove to yourself that they yield the same results.

Solution by matrices

To tackle this problem using matrices you first need to arrange your equations:

$$

\begin{aligned}

I_1&& -I_2&& -I_3&& =&& 0&& \\ \\

-8I_1&& -6I_2&& && =&& -30&& \\ \\

&& 6I_2&& -3I_3&& =&& 0&& \\ \\

\end{aligned}

$$

This structures the coefficients of each variable in a manner that permits you to construct the matrix equation:

$$

\begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1& -1 \\ -8 & -6 & 0 \\ 0 & 6 & -3 \end{bmatrix}

\begin{bmatrix} I_1 \\ I_2 \\ I_3 \end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ -30 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}

$$

From there, either you perform row manipulations to arrive at a solution, or you find the inverse of this left matrix, and the solution falls out:

$$

\begin{bmatrix} I_1 \\ I_2 \\ I_3 \end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix} 1 & -1& -1 \\ -8 & -6 & 0 \\ 0 & 6 & -3 \end{bmatrix}^{-1}

\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ -30 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}

=

\begin{bmatrix} 3 \\ 1 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix}

$$

Solution by substitution

If you do substitute \$I_1=I_2+I_3\$ into the KVL equations, you reduce the problem to two simultaneous equations:

$$

\begin{aligned}

-14I_2&& - 8I_3&& =&& -30 \\ \\

6I_2&& - 3I_3&& =&& 0 \\ \\

\end{aligned}

$$

Again, what you do with this is up to you, but I will perform another substitution in an attempt to eliminate \$I_3\$. Rearranging the second equation:

$$

\begin{aligned}

6I_2 - 3I_3 &= 0 \\ \\

3I_3 &= 6I_2 \\ \\

I_3 &= 2I_2 \\ \\

\end{aligned}

$$

A final substitution will reveal \$I_2\$

$$

\begin{aligned}

-14I_2 - 8(2I_2) &= -30 \\ \\

-30I_2 &= -30 \\ \\

I_2 &= 1

\end{aligned}

$$

Therefore:

$$

\begin{aligned}

I_3 &= 2I_2 \\ \\

&= 2 \\ \\

I_1 &= I_2 + I_3 \\ \\

&= 3

\end{aligned}

$$

As you can see, the solution by substitution agrees with the matrix solution.

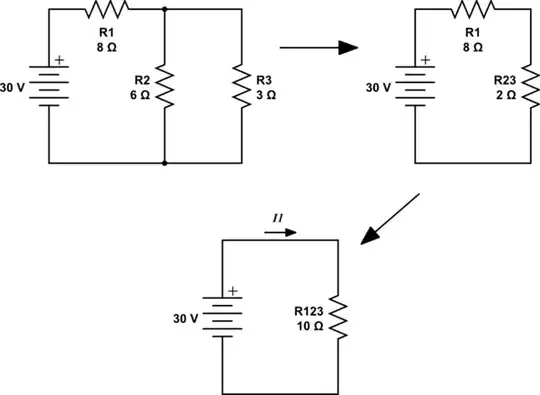

Verification by element composition

If I'm honest with you, I wasn't sure about these prior solutions, so I just did a quick simplification of your circuit, which is easy when you notice that \$R_2\$ and \$R_3\$ are in parallel. By composing a single resistance \$R_{23}\$ from that pair, verification of my calculation of \$I_1\$ is trivial:

$$ R_{23} = R_2 \parallel R_3 = \frac{R_2 \times R_3}{R_2 + R_3} = \frac{18}{9} = 2\Omega $$

\$R_{23}\$ is in series with \$R_1\$, so we can combine them into a single resistance \$R_{123}\$:

$$ R_{123} = R_1 + R_{23} = 10\Omega $$

simulate this circuit – Schematic created using CircuitLab

A quick application of Ohm's law reveals \$I_1\$:

$$ I_1 = \frac{30V}{10\Omega} = 3A $$

Now I'm convinced that the value I derived above for \$I_3\$ is correct.

By inspection I can see that since \$R_2\$ and \$R_3\$ are in parallel, then the voltage across them must be the same. The current through them must therefore be (inversely) related by their resistances. Without doing any maths, I can tell straight away that the current \$I_2\$ through 6Ω must be half of the current \$I_3\$ through 3Ω.

Knowing the sum of these currents to be \$3A\$, in my head I can work out that \$I_2=1A\$ and \$I_3=2A\$, which all agrees with the values I found before, using less inuitive approaches.

Conclusion

The answer to your question is: You can use any method you like to attack this problem. You may obtain equations from Ohm's and Kirchhoff's laws, and solve the resulting simultaneous equations either by substitution or by any matrix technique. Or, in many cases, you may use component composition to simplify circuits, and apply Ohm's law alone to reveal circuit state.

The results of all these techniques must necessarily agree with each other, since at their heart they are all describing the system using the same underlying algebraic principles.