How do LEDs conserve their state? I'm pretty sure each LED is powered thanks to decoders, but decoders cannot keep a steady power flow through each; every cycle can only light one LED. But once the cycle moves on, how does this led preserve it's state? Does every pixel have a flipflop gate? Is it something else? And am I even correct about the way pixels are wired?

-

5Welcome! What LEDs are we talking about? – winny Jul 12 '23 at 17:35

-

Oleds I think? Honestly if you can tell me whatever top 3 type of LEDs we find on modern displays, that's fine. – qkasriel Jul 12 '23 at 17:44

-

1Please clarify. In which application? – winny Jul 12 '23 at 18:00

-

What LEDs or what pixels you are talking about? Addressable LEDs used in LED strips perhaps? Something else? LED screen? – Justme Jul 12 '23 at 18:08

-

Plain LEDs do not "conserve their state" - they only light as long as power is applied. There are "addressable LEDs" that include an IC that will store the last programmed state of the LED as long as power is applied. – Peter Bennett Jul 12 '23 at 20:07

-

Most displays with LEDs just have LEDs as background light. Obviously a LED needs a driver circuit which keeps the LED at wanted brightness. The LED just emits light as per current driven to it. – Justme Jul 12 '23 at 21:05

4 Answers

They don't conserve their state. They rely on persistence of vision. This is the same thing that makes us be able to see films that show one frame at a time. If the frame rate is faster than our eyes and brains can process, our vision will tend to see them as one continuous moving image. The same thing happens with a CRT television or a multiplexed LED array, they flash, but it's so fast that we don't notice it.

This also happens with LEDs that are pulse width modulated, in videos you can often see car tail lights and other LED lights that flash because the PWM rate and video rate are out of sync. We see the lights as being steady but they're really flashing very quickly.

Also, a cycle can light more than one LED at a time. Take a multiplexed 7 segment LED display for example, each cycle enables one digit, but each digit can have from 0 to 7 segments lit at once.

- 22,826

- 1

- 20

- 58

-

-

While mostly correct for discrete LED emitters, this isn't strictly true for LCD, in which the polarising liquid crystal orientation is retained between refresh cycles, or in most OLED technologies (e.g. AMOLED), in which a tiny capacitor retains enough charge to continually power each tiny emissive element between refresh cycles. – Polynomial Jul 12 '23 at 19:57

It depends!

For many types of display technology, pixels don't retain brightness continuously - your eyes do.

Your eyes have rods and cones in the back, which act as biochemical photoreceptors for luminescence and colour respectively. Their response speed is pretty fast, but it isn't instantaneous. This results in a form of image retention, called persistence of vision. If you apply an optical stimulus and then take it away very quickly, your eye (and the optical processing pathways in your brain) can't keep up and your vision instead responds as if you're seeing an average of the two states. The exact details of are deeply complex, but they form a key basis for almost all modern colourimetery standards used in lighting and display technologies.

The simplest application of this is pulse width modulation (PWM) of LEDs. Imagine you have an LED turning on for half a second, then off for half a second, i.e. flashing at 1Hz. You can see the LED being fully on, then fully off. Now imagine that you increase the frequency at which the LED flashes, while you try to say "on" and "off" in response to what you see. Eventually it's so fast that you can't keep up with the words, and it looks like a strobe. Keep going, and the LED is flashing on and off so quickly that you can't actually tell if it's flashing at all. However, it now appears to be dimmer than it was when it was just switched fully on.

Now imagine that you keep switching the LED on and off at a fairly high frequency (say 2kHz) but you adjust the ratio between the amount of time the LED spends switched on, and the amount of time the LED spends switched off. This is known as the duty cycle - a duty cycle of 0% means the LED is fully off, a duty cycle of 50% means the LED spends equal time on and off, and 100% means the LED is fully on. Your persistence of vision causes this to be averaged into varying brightness.

There's a complexity here - your eyes don't perceive brightness linearly, with greater sensitivity to changes in brightness at the dimmer end of the scale, so we typically need to apply gamma correction or an electro-optical transfer function (EOTF). This gets pretty complicated to explain so I'll leave that as out of scope for this answer.

This isn't to say that LEDs must be PWM'd in order to dim them. You can also use a constant-current driver, in which the power being delivered to the LED is modulated directly without actually switching the LED on and off. A common approach is a linear constant current driver - this is akin to putting a variable resistor in series with the LED, such that some power is consumed in the resistor as heat instead of in the LED as light. This approach is simple and produces low-noise results, but it is inefficient. Another approach is to use a switch-mode driver, which is essentially just a switch-mode power supply operating in constant current mode. This is similar to driving LEDs with PWM, but the constant current driver's inductor and output capacitor act like a low-pass filter to produce a fairly steady drive current instead of an on/off waveform. This is more efficient than a linear driver, but has increased design complexity.

You mentioned LED matrices, so let's use that as our next example:

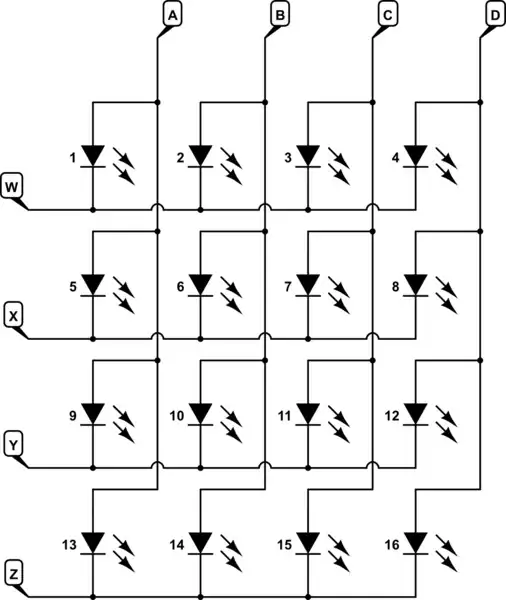

simulate this circuit – Schematic created using CircuitLab

Let's say we want to light up LED 6. We connect B to a positive voltage and X to ground. A current flows from B, through LED 6, to X, lighting up LED 6. Easy! Now imagine we want to light up the first and third columns (the odd numbered LEDs), but the supply we're using can only handle enough current to light up 4 LEDs at once. We can't just set W, X, Y, and Z low and A and C high, because that'd turn on eight LEDs at once and use too much current.

Instead, we can quickly set just A high, then just B, then just C, and so on, very quickly, and configure the W, X, Y, and Z lines as needed to light up specific LEDs. We refer to this as scanning. At any one point in time the power supply only has to power a maximum of four LEDs, and only those LEDs are actually emitting light, but if you do it quickly enough your eyes will not see this happening due to their persistence of vision. The downside here is that the maximum brightness is lowered because each LED is switched on for only a short amount of time during the scanning process - in this 4x4 array each LED can only be switched on for 1/4 the time. Luckily, due to the nonlinear way we perceive brightness, an LED being switched with a duty cycle of 1/4 (25%) actually appears to be about 55% of its full brightness.

However, with very big LED matrices (like LED display panels) this is obviously untenable - if you had 100 rows you'd only be able to switch each column on for 1% of the time, which would make it extremely dim. In addition, the number of column and row lines becomes way too much to drive directly from a microcontroller. There are a few ways to solve this. One option is to ensure that the power supply can drive all the LEDs at once, then use latching shift registers to update the column and row lines from a serial bus. Another option is to split the matrix into chunks and scan each "chunk" like its own matrix, which kinda "distributes" the scanning effect so you have multiple rows and columns active at once but still get power savings from only actually lighting up a fraction of the LEDs at any one time. Your persistence of vision again hides this scanning effect.

Other display technologies utilise a combination of persistence effects. CRT displays accelerate high energy electrons toward a phosphor-coated screen, using electric actuators to "steer" the beam position. When the electrons strike the screen, the phosphor luminesces in a phenomenon called phosphorescence. However, the beam only strikes one point on the screen at once. The beam is "scanned" horizontally across the screen, then moves one "pixel" down and reverts to starting horizontal position, and scans the next line. The phosphor itself continues to phosphoresce for a short time after being struck, leading to a small amount of image persistence. However, this afterglow-like persistence typically only lasts for a few tens of microseconds, whereas it takes around 17-20ms to "draw" an image that covers the whole screen. Your persistence of vision does the rest of the job, allowing you to see the full image despite only a tiny portion of it ever actually appearing at once.

This is also why analogue TV standards like PAL and NTSC used interlaced scanning rather than progressive scanning. In progressive scanning, you draw line 1, then 2, then 3, then 4, until you've finished drawing all the lines. In interlaced scanning, you draw all the odd numbered lines first, then go back and fill in all the even numbered lines (or vice versa). These are called the odd and even fields. This interlacing ensures that the whole screen is filled with one field in half the time it takes to draw a complete frame, before the remaining detail is filled in by the other field. This exploits the averaging effect of your persistence of vision to make the image feel more responsive and less flickery than it would with progressive scanning.

Not all LEDs are direct emitters. Some LEDs, particularly large white LEDs, consist of an LED emitter with a phosphor layer on top that phosphoresces when illuminated. These are often referred to as "PC" (phosphor coated) LEDs; in LED series designed for colorimetric accuracy you'll often see stuff like "Amber" and "PC Amber" as options, indicating that one uses a direct amber emitter (typically closer to monochromatic light) and another uses a phosphor coating (typically broader spectrum). These PC LEDs are advantageous in some cases because they allow for spatial diffusion of light from emitter arrays (as seen in COB LEDs) and may allow for broader spectral output in wavelengths that can't typically be directly generated via semiconductor electroluminescence (e.g. due to the green band gap phenomenon). These phosphor coatings themselves exhibit a small amount of persistence - perhaps a microsecond or so of "afterglow" after current ceases to be applied - akin to the persistence effect in the phosphor coated panel of a CRT display. This persistence is usually not a significant factor - the timescale of your persistence of vision is far longer - but it can occasionally be relevant if you're trying to design very high bit-depth linear space PWM drivers, or PWM drivers with very high switching frequencies (e.g. suitable for both general illumination and high speed camera work), due to the very short pulse timings at the duty cycle extremes.

LCD technologies take a different approach to displaying images. Each pixel is actually just a tiny switchable light filter (in the form of a liquid crystal) with no ability to emit light on its own. A backlight (typically CFL or LED) sits behind the LCD panel, with a polarising filter, continuously emitting polarised white light. The display driver circuitry scans through all the pixels in the LCD panel, electrically adjusting the orientation of the tiny liquid crystals in sequence. The amount of polarised light blocked vs. transmitted by the crystal is altered in this manner, producing a dimming effect. Unlike with CRT, the whole display is lit up all the time, and the full image persists on screen. Your persistence of vision is still exploited a little, though. As a frame is being drawn you've got part of the current frame being displayed and part of the old frame being displayed. This process is fast enough that you typically don't notice it, and your vision retains the image on the previous frame while simultaneously being able to react to the updated picture - often even before you've consciously processed and understood the complete image. The cognition involved here is pretty incredible, but it's a whole field of study and way out of scope for this answer.

Some LCD displays dim the backlight to limit the amount of light bleed (light transmitted through liquid crystals that are "off") depending on the image. Others use an array of local LED backlights that can be independently dimmed to produce a greater contrast ratio, making the darker portions of the picture appear darker while the brighter portions appear brighter. This dimming is typically achieved in exactly the same way I described earlier in this answer - either PWM or a switching CC driver.

OLED is pretty difficult to describe in this context because it isn't actually one technology, but a whole family of them, each with their own properties. A commonality is that each pixel produces its own light, rather than subtracting from a backlight like an LCD does. Most OLED displays use a thin film transistor (TFT) array to charge tiny capacitors which provide enough energy to power each individual OLED emitter before the next refresh cycle. This means that the pixels do in fact fully persist their state, remaining lit up between updates, not relying on your persistence of vision to retain the image (although inter-frame retention still applies like it does with LCD). If you want to read more on this front, the easiest OLED tech to understand is probably AMOLED.

There are also new technologies like microLED, QDEF, QDCC, QD-LED (aka EL-QLED) which use quantum dot semiconductor nanocrystals as a method to produce monochromatic (single-wavelength) light, either subtractively or emissively. These are quite a lot to dig into, in part because they're emerging technologies, and this answer is already really long so I'll skip these.

Finally, I feel like I need to quickly mention some technologies that don't use progressive or interlaced scanning. These would be film projectors and DLP projectors. Film projectors are globally scanned, which makes sense if you think about it - each frame of the film is moved into place and light from the projector bulb flashes through it, revealing the whole frame all at once. Your eyes' persistence of vision compensates for the small time between frames where the bulb is occluded and the next frame of film is mechanically moved into place. DLP projectors use a MEMS array of micromirrors to direct incoming light either towards or away the projector lens. The micromirror positions can all be updated simultaneously (or near enough to it) resulting in the whole image being updated at once. However, in order to display colour images, most DLP projector technology splits each frame into three subframes, showing the red, green, and blue components (and often a supplementary white component) of each frame sequentially. Others use alternate subframe colour schemes like CMY. Your persistence of vision averages these out to a single full-colour image.

- 10,691

- 5

- 49

- 88

-

Side note not strictly about raster display technologies: persistence of vision is also the phenomenon used to make laser shows work. The laser beam (either a single colour, or multiple separate colour beams combined and collimated together) is shined against a mirror galvanometer assembly (often referred to as a "galvo" or "scanner") which allows for the emitted beam angle to be controlled in the X and Y planes at high speed. Just like in a CRT, our persistence of vision turns that single moving beam into a much more complex retained image. – Polynomial Jul 12 '23 at 20:23

-

1Quite Illuminating! DLP is also interesting in that it relies on PWM for brightness because the mirrors only make useful light when fully in the on position. Some very high end projectors use multiple digital micromirror devices to allow you to get R, G, and B at the same time but still end up requiring POV because of the PWM. – artemist Jul 12 '23 at 20:34

Let’s assume you’re talking about a multiplexed display, where groups of LEDs (e.g., the four digits on a clock) are illuminated one at a time.

The display controller holds the state of each displayed pixel (or digit segment) in an internal memory. This memory is the thing that 'conserves' each LED's state. The controller reads its memory and outputs each multiplex group (e.g., a clock digit) at a rate fast enough so that the eye cannot see the changeover.

The multiplexed display fools the human eye into seeing more than one element at a time, through a phenomenon called persistence of vision. Basically, the eye sees the the rapid event (the clock digit being illuminated), which 'persists' in the brain as an after-image for longer than the actual event. So it's your eye and brain that 'remembers' what the lit digit looked like, at least for a short time; you perceive it as a steady digit.

Read a bit more about persistence of vision here: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/persistence-of-vision-explained

The display multiplexing rate is commonly called the refresh rate. For a multiplex to appear steady without flicker, the refresh rate has to be above 25Hz or so (and, to complicate matters, this varies widely depending on viewing environment.) This frequency is called the flicker fusion threshold; closely related to persistence of vision.

To avoid flicker, most LED display multiplexing is much faster than that. For a small display like a clock the refresh rate might be hundreds of Hz.

A high speed camera can be set up to see the multiplexing action, showing each digit illuminated one at a time. But the eye cannot see this - human eyes are too slow to pick it up.

Why bother with multiplexing? Simple answer: cost and power. Multiplexed displays can get by with fewer drivers and wires than non-multiplex ones (reducing cost), and will consume less power because not all the LEDs are on at the same time.

The drawback to display multiplexing is that in some cases this can result in flicker, especially for large-area displays in bright environments. The switching action can also cause EMI problems, a huge issue for LED clocks with radios (later ones changed over to direct-drive displays for this reason.)

Another multiplexing problem area is with cameras: the display multiplex action can strobe with the the camera frame rate, causing waves of uneven illumination to appear on the recorded video. (This also happens when pulse-width modulation is used to control LED brightness, such as on automobile lights.) This is especially an issue when the camera uses a fast shutter rate.

- 53,912

- 2

- 49

- 152

Most modern displays (with the exception of smartphones) are LCDs, which do not have LEDs in the pixel. Rather each pixel is a color filter in front of a white backlight. A liquid crystal can modulate the amount of light through each pixel with its state held by a thin film transistor.

In modern LCDs the backlight is usually an LED, but it can also be a fluorescent light or even no light at all in the case of old reflective LCDs. Separating the pixel from the LED may seem strange, but it addresses the problem you identified: LEDs are tricky to control and retain state. Separating the pixel (which must remember its state for at least as long as the frame time) from the LED (which can be left simply on all the time) simplifies design.

- 16,883

- 1

- 21

- 46