Summary: The Fe-C system, and thus steel, is unique due to a eutectoid transformation from a high-solubility phase to a low solubility phase that allows for a wide variety of microstructures and properties which are highly and relatively easily tunable. Other first-row transition metals have different, and less exploitable, behavior when alloyed with carbon.

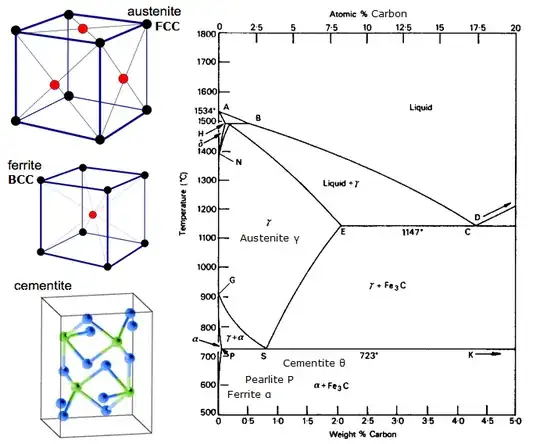

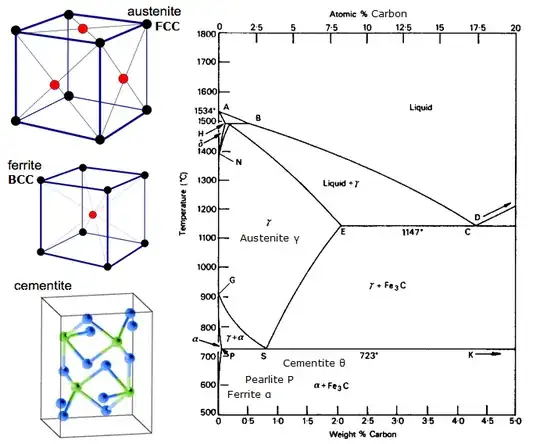

Fe-C is the only first-row transition metal-carbon system that has a eutectoid transformation in its phase diagram.The eutectoid transformation changes austenite to ferrite and cementite on cooling. Austenite has high carbon solubility, and ferrite has low carbon solubility. I am picking on first-row transition metals as they tend to have chemical behavior "close" to that of steel, with similar cost, density, and other "obvious" properties (with the exception of scandium, which is extremely rare and expensive), and examining all 70+ metals is a fair amount of work for this answer.

The nature of the eutectoid transformation allows for many microstructures and thus a high degree of tunable properties. Consider a eutectoid steel austenitized and cooled at varying rates:

- If cooled slowly, a moderately ductile, moderately strong pearlite microstructure forms. Pearlite results from a cooperative nulceation and growth process as carbon leaves austenite during its transformation to ferrite, forming alternating lamellae of ferrite and cementite.

- If cooled moderately rapidly and then held isothermally for a period of time, a much harder bainite microstructure forms. The kinetics of bainite formation are not well understood, but the microstructure is a less-organized arrangement of cementite and ferrite, again resulting from carbon coming out of solution as austenite transforms into ferrite.

- If cooled extremely rapidly, an extremely strong and hard martensite microstructure forms. Martensite formation is a diffusionless process in which carbon is trapped in austenite while it transforms to a BCC structure, distorting the lattice into a strained BCT structure which is difficult to strain further, hence its high strength. By altering the quantity of carbon and being creative with heat treatment schedules, a wide array of microstructural combinations are available.

With appropriate alloying and heat treatment, it is possible to have a steel with retained austenite, ferrite, pearlite, bainite and martensite all in the same material. Such complex microstructures are impossible in other first-row transition metal-carbon systems.

All of the wide heat-treatability and wide array of microstructures and properties are entirely due to the presence of a eutectoid transformation which takes a high-solubility phase to a low-solubility phase. The eutectoid transformation itself is due to a phase change from austenite (FCC) to ferrite (BCC) and the resulting significant loss of carbon solubility. The answer to your question is effectively no, there are no other alloys (of which I am aware) that behave like steel during processing. The answer to your alternate question is that carbon has less useful and less exploitable effects on other first-row transition metals.

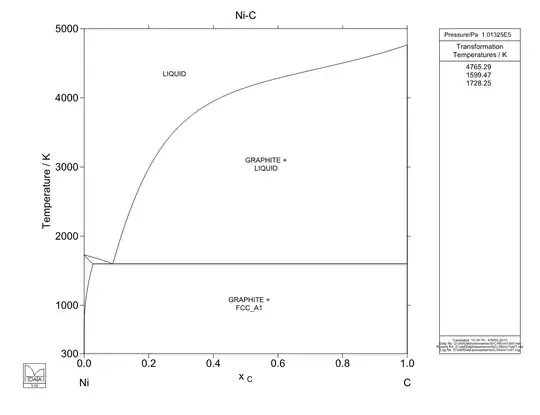

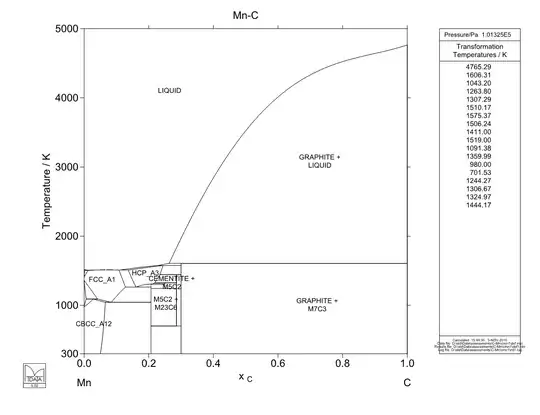

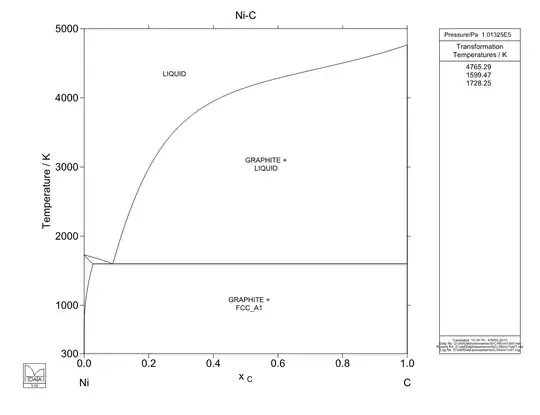

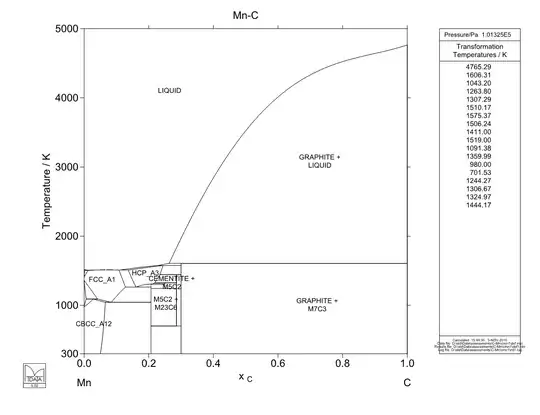

Below are the Fe-C, Ni-C and Mn-C phase diagrams for comparison. Note that the Fe-C phase diagram stops at 0.2 a/a C while the others go to 1.0 a/a C. Ni-C has no eutectoid, only a eutectic transformation, and thus can only be precipitation hardened. Any other microstructure formation would have to occur during solidification. Mn-C phase diagram has a eutectoid, but it goes from a high-solubility phase to another high-solubility phase, which means that extremely large amounts of carbon would be present in the lower temperature phase (nearly 10% a/a C compared with less than 1% a/a C in steel), which would result in extreme brittleness.