Both watts and volt-amps come from the same equation, $P=IV$, but the difference is how they're measured.

To get volt-amps, you multiply root mean square (RMS) voltage ($V$) with RMS current ($I$) with no regard for the timing/phasing between them. This is what the wiring and pretty much all electrical/electronic components have to deal with.

To get watts, you multiply instantaneous voltage ($V$) with instantaneous current ($I$) for every sample, then average those results. This is the energy that is actually transferred.

Now to compare the two measurements:

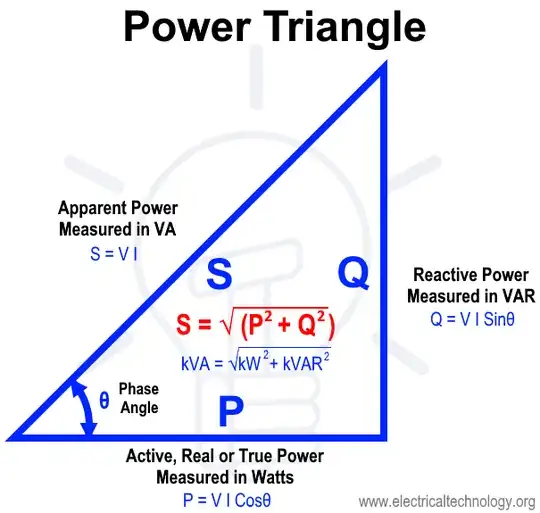

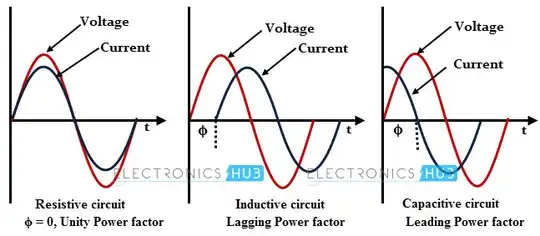

If voltage and current are both sinewaves, then $\text{watts} = \text{volt-amps} \times \cos(\phi)$, where $\phi$ is the phase angle between voltage and current. It's pretty easy to see from this that if they're both sine waves and if they're in phase ($\phi = 0$), then $\text{watts} = \text{volt-amps}$.

However, if you're NOT dealing with sine waves, the $\cos(\phi)$ relationship no longer applies! So you have to go the long way around and actually do the measurements as described here.

How might that happen? Easy. DC power supplies. They're everywhere, including battery chargers, and the vast majority of them only draw current at the peak of the AC voltage waveform because that's the only time that their filter capacitors are otherwise less than the input voltage. So they draw a big spike of current to recharge the caps, starting just before the voltage peak and ending right at the voltage peak, and then they draw nothing until the next peak.

And of course there's an exception to this rule also, and that is Power Factor Correction (PFC). DC power supplies with PFC are specialized switching power supplies that end up producing more DC voltage than the highest AC peak, and they do it in such a way that their input current follows the input voltage almost exactly. Of course, this is only an approximation, but the goal is to get a close enough match that the $\cos(\phi)$ shortcut becomes acceptably close to accurate, with $\phi \approx 0$. Then, given this high voltage DC, a secondary switching supply produces what is actually required by the circuit being powered.