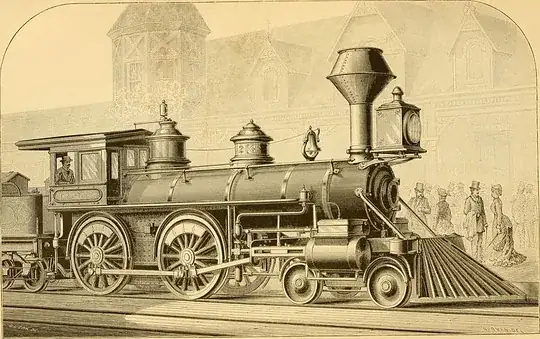

Steam locomotives use steam pistons, not steam turbines.

Gears/cogs would be pointless since there is no rotary source of power on steam locomotives. They use steam pistons, which go back and forth.

As the physics worked out, direct-drive worked out really well with achievable values of piston diameter, stroke/eccentric, and wheel size. Until it didn't. And what got them was the curves.

Mainline pullers stuck with rods: way too big for gears

As fully superheated boilers became very powerful, fast passenger locomotives used this power at higher speeds. For them, the side-rod design was perfect. But slow lugging freight locomotives needed more weight on the rail to transfer the power at low speeds. This required more driving axles to spread the weight. That made a single rigid group of driving axles too long for curves. So they split into two (rarely, three) groups of driving axles. Power transfer was done with an engine on each group, usually simple, sometimes compound. Union Pacific's Big Boy had 8 drive axles in two groups (each with a simple engine, still avoiding gears), handling curves like a 4-drive-axle locomotive.

src

src

Taken to absurdity. The Virginian Railway finally gave up and electrified.

At these power levels, 4000-6000 horsepower, gear drive was out of the question: it was an order of magnitude too much power for gears. Even the electric GG1 of the era used twelve massive pinions to transfer a similar amount of power to six axles.

Much smaller engines could be geared

Mountain railroads used low power, lightweight locomotives which had to slither up fairly tight curves. Even a very modest side-rod steam engine was too stiff for the curves. They also wasted a lot of precious weight on non-drive wheels, e.g. the pilot truck and the tender. Ephraim Shay solved this problem with, indeed, geared locomotives. Keep in mind these are small locomotives: the largest, Western Maryland #6, has boiler pressure of 200 psi and a top speed of 23 mph.

Ephraim Shay put a drive shaft along one side of the locomotive, gearing to each wheel. The pistons directly cranked the drive shaft. Note the elaborate telescoping drive shafts, most especially important due to its off-center location.

Note the gears. sources

Note the gears. sources

Charles Heisler put the drive shaft down the locomotive centerline, and used a "vee-twin" piston arrangement. Note the side rods: that means only one of the two axles is geared to the drive shaft, the side rods transfer power to the other axle. Side rods like that imply perhaps 100 horsepower per axle.

The Climax Manufacturing Co. took Heisler's centerline-shaft arrangement and added a cross-shaft and more gearing to put the steam pistons in an almost conventional location.

Having seen these geared-locomotive arrangements, you can see where they would not "scale" up to multithousand horsepower outputs.