The explanation is due to the fundamental physics of momentum transfer. In all cases of continuum flow, including laminar, transition, and turbulent flow, the zero (no-slip) boundary condition applies where the fluid touches the wall. Since there is fluid flow in regions removed from this boundary, momentum must be transmitted in these regions - called the boundary layer - to bring the free stream value for velocity down to zero.

With laminar flow, which applies down to zero free stream velocity, momentum transfer is molecule to molecule, and at a scale that is much smaller than any roughness at the wall. Thus, whether the laminar boundary layer is larger than the roughness does not provide an explanation for the question. The only way roughness can affect molecular momentum transfer is if the roughness itself is at the same molecular scale, and in that case (which does exist) the effect of roughness is, well, at the molecular scale, which is the laminar regime; i.e., it's a null effect.

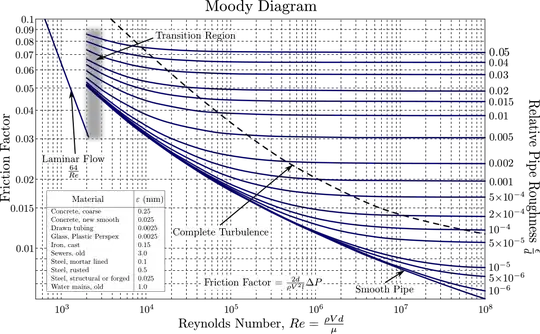

Thus, roughness can affect the shear stress at the wall only if it's large enough to participate in turbulence, and the scale for that is orders of magnitude larger than the molecular scale. But roughness scale alone isn't sufficient to cause turbulence, as we see from the Moody chart Mart provided. The Reynolds Number must also be sufficiently large.

In turbulent flow, momentum is transferred between little clumps of fluid, which is orders of magnitude in scale larger than the molecular scale. Consider now the laminar sub layer that exists at the molecular scale, again, much smaller than any significant roughness scale, or turbulent scale. By "significant" I mean both large enough scale and large enough Re. In this case, the sub layer laminar flow is very tortuous, able to follow the roughness, until the momentum of the molecular flow cannot negotiate the tortuous path; i.e., until Re becomes large enough. At that point, little clumps of fluid break away from the more ordered molecular flow, and this is what we call turbulence.

Bear in mind that there is always an "entrance region" where a free stream first encounters an obstacle, either in internal flow, as in a pipe, or in external flow, as on an airplane wing, or the well understood "flat plate." If the free stream contains no turbulence (a "quiescent flow") there will always be laminar flow at the beginning of this entrance region. With external flow, the characteristic length for Re is distance along the wing or plate from the "leading edge." Thus, at the beginning, Re is very small, hence the flow is laminar, regardless of roughness. With internal flow, the characteristic length for Re is pipe diameter, and the Moody chart applies only for the "fully developed" regions of pipe flow. In the entrance region of pipe flow, which begins as an "external flow," the boundary layer grows at first like it does over a flat plate, and there, Re characteristic length is again distance from the leading edge. But as the boundary layer grows, it meets with the boundary layer growing from other areas along the pipe circumference. At that point, the entire flow is boundary layer flow and is considered fully developed.