The effects of heating-quenching a metal is explained below

Transformation hardening is the heat-quench-tempering heat treatment cycle addressed earlier in this article. It's used to adjust strength and ductility to meet specific application requirements. There are three steps to transformation hardening:

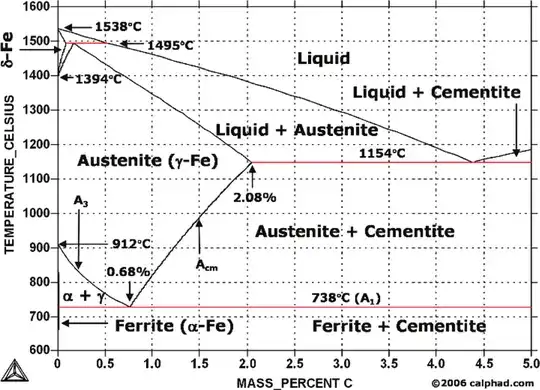

Cause the steel to become completely austenitic by heating it 50 to 100 degrees F above its A3-Acm transformation temperature (from that steel's iron-carbon diagram). This is called austenitizing.

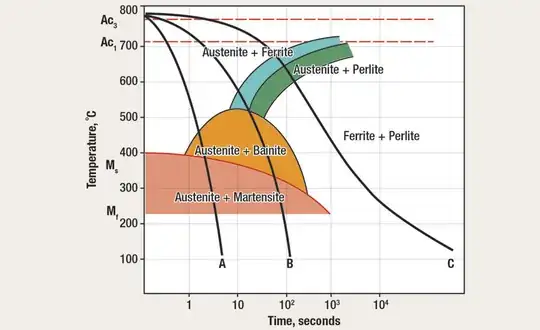

Quench the steel; that is, cool it so fast that the equilibrium materials of pearlite and ferrite (or pearlite and cementite) can't form, and the only thing left is the transitional structure martensite. The idea here is to form 100 percent martensite.

Reduce brittleness by tempering the martensitic steel, which requires heating it, but keep temperatures below A1. Typically, this means temperatures are between 400 and 1,300 degrees F, which allows some of the martensite to turn into pearlite and cementite. Then allow the piece to air-cool slowly.

By using the proper heat treatment and choosing a steel with just the right amount of carbon, you can get just about any combination of hardness and ductility to meet a specific requirement. Remember, the more pearlite and cementite that forms, the more ductile and less brittle the steel will be. Conversely, more martensite means less ductility but more hardness.

One topic has been ignored up to this point is grain structure changes during precipitation hardening. A steel's grain size depends on the austenitizing temperature. When a steel that will transform is heated to slightly above its A3temperature and then cooled to room temperature, grain refinement takes place. Fine grain size offers better toughness and ductility.

Metallurgy Matters: Making steels stronger