I recently learned that every axle on a modern train has brakes. In the past, I had assumed that only locomotives and cabooses had brakes, and assumed that was the reason for the commonly known long stopping distance of trains.

This new discovery got me to thinking: if every car has brakes, every car can stop itself. If each car is stopping itself, then each car could brake at the same deceleration such that there is no force (push or pull) on the couplers to the cars ahead and behind. If that is true, then the train could be treated as a sequence of independent closely spaced vehicles with a small amount of space between them. Treating each train car independently gives the mental image of lone car rolling down a track. That mental image looks similar (in a spherical cows way) to a truck to me, and prompts me to ask, "if this train car was equipped with a modern braking control system (like ABS in vehicles), why couldn't it be expected to be able to stop in the same distance as a truck? And if that is true, why can't the whole train be expected to stop in the same distance as a truck?"

Some of my assumptions in those questions are that the train and truck are:

- the truck and train are stopping from the same speed (lets say 75 mph or 120 km/h since that's freeways speeds here)

- We can redesign anything on the train locomotives and cars, including to use modern technology (like ABS type brake controllers or data signalling between train cars)

- the design of the rails, ties, track bed stays the same

- the railroad (and structures underneath it like bridges) can take the imposed horizontal load without failing. The rails don't topple, detach from the ties, splay out widening the gauge, etc.

- the braking control system keeps the wheel/rail interface in static friction and all dynamic friction/sliding happens at the independent shoe/drum interface

- The braking drum or disk can be separate from the wheel since we can redesign the train car

Thinking on this for a while, I realized the coefficient of friction could play a factor:

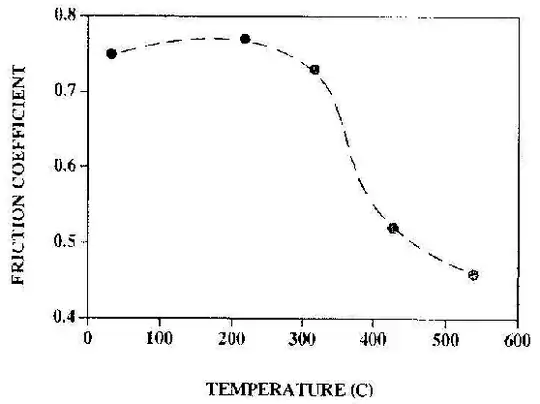

According to this page https://www.engineeringtoolbox.com/friction-coefficients-d_778.html clean/dry steel on steel has a (static) friction coefficient of 0.5 to 0.8 and a tire on a dry road has 1.0 or so.

Trains weight more, BUT the normal force for placed on the wheels should go up in direct proportion. If the (max braking) force of friction is the coefficient times the normal force, then I would expect that the max braking force would also proportionally go up with more weight.

So it seems like the only thing different between a heavily loaded truck and train affecting the (max braking) force you could generate is the coefficient of friction. Because this is about half, I would expect the braking force to be half.

Kinetic energy is 1/2 * mass * (velocity)2, which gives you units of joules. As a unit, joules can be re-written as newtons of force through meters of distance. If we have half as many newtons (because half as much coefficient of friction for steel on steel vs tire on pavement) we could assume 2 times the number of meters to stop the same mass.

On top of that, it seems that increasing the mass wouldn't increase stopping distance (assuming the brakes and discs survive the increased energy dissipated): an increase in mass should proportionally increase the kinetic energy AND the maximum static friction (= max braking force), causing the two to cancel for a same stopping distance.

So why is it "common knowledge" that trains have to take miles to stop but not trucks? Assuming that the braking systems on a train car had the controls a truck does to stay in static friction (anti-lock braking) why can a train car not be expected to stop in about 2x the distance of a truck (in ideal conditions, of course)? And if that can be expected, why can't we expect a whole train of train cars to stop in about 2x the distance of a truck?

(And maybe it could be even less than 2x the distance if the train can do eddy current braking to the rails or use magnetic fields to "clamp" the car to the rails, where a truck has no such option.)

$ m^2$" />

$ m^2$" /> $2 v_0$" />

$2 v_0$" />