tl;dr: Very windy days might be worse but the data isn't great. Charging in the late afternoon is your best bet to reduce marginal emissions.

From the question:

On the other hand, plugging my car into the grid presumably increases the load, which will be supplied by non-renewable generation (since renewables don't yet cover 100% of demand).

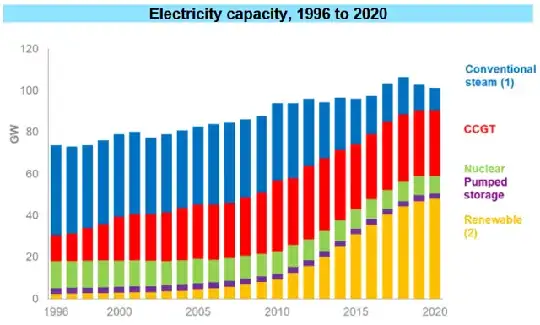

What you have described is the marginal energy -- basically, which power source will be adjusted in response to a change in demand. This is determined by a complicated mix of physics, engineering, market forces, and, of course, weather, however by analyzing historical data it's possible to determine how this varies with time, without needing to understand all the complicated factors that influence it.

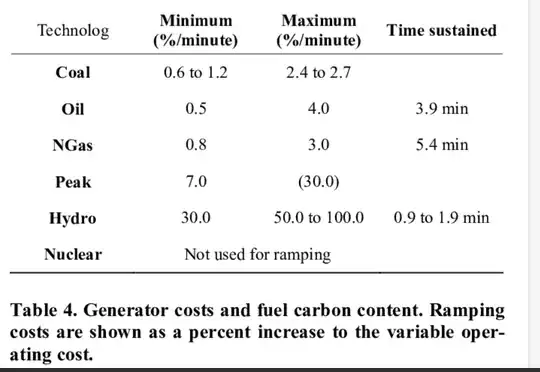

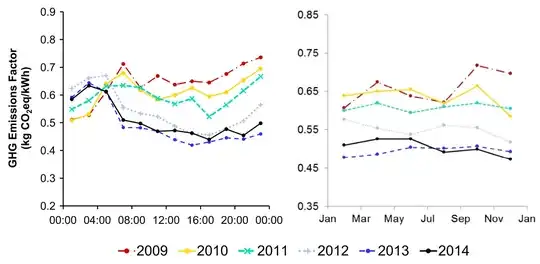

The paper "Marginal greenhouse gas emissions displacement of wind power in Great Britain" provides an analysis of the marginal emissions factors considering both time of day and month of the year.

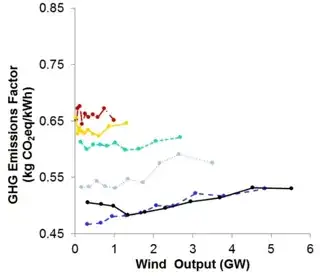

The charts below show the marginal emissions factors (MEF) for 2009 (in red) through 2014 (in black). You can see that as wind power capacity is added to the grid over time, the overall MEF has dropped, but there are still daily and seasonal variations.

Specifically, it would be best to charge during the late afternoon in December, when the MEF is lowest.

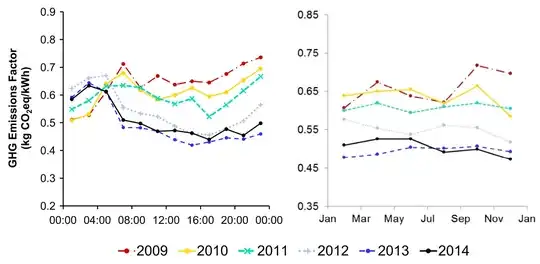

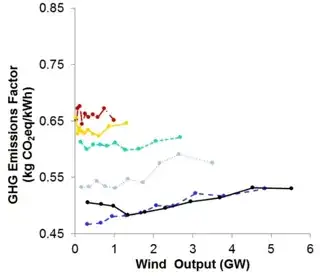

Another interesting result from the paper is that as the wind output to the grid in any moment increases, the MEF also increases:

This actually indicates that charging could be best when there's a medium amount of wind -- not on the windiest days. The paper speculates that the reason for this trend is that high wind output correlates with high system demand, meaning that most gas plants are already online, and a higher proportion of marginal energy is actually coming from coal plants.

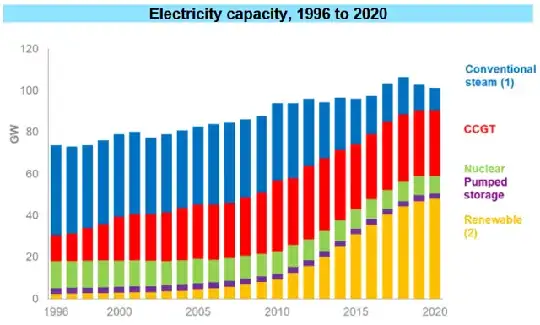

However, this paper is from 2014, and there have been significant changes to the grid makeup since then. From UK Energy Brief, 2021, you can see that coal capacity ("conventional steam") has reduced by nearly half, while renewable (mostly wind) has nearly doubled.

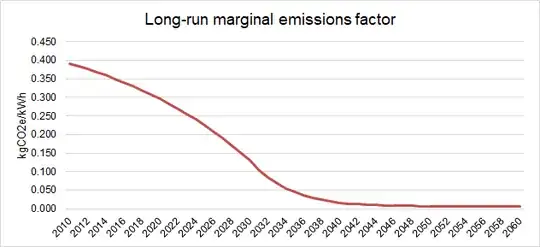

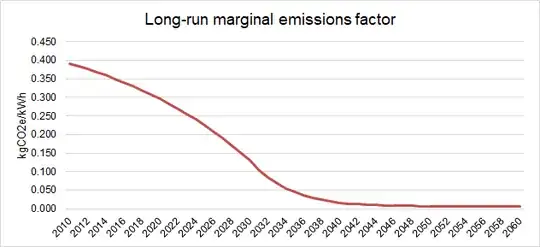

Further, the UK government forecasts the long-run marginal emissions factor for the overall grid, out to 2100. "Long-run" just refers to a permanent change, more useful for long term planning and analysis. The data is available here: Green Book supplementary guidance: valuation of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions for appraisal . I put together a chart showing how the emissions factor is expected to change over time:

From this we can see that as renewable penetration on the grid increases, the timing of when power is used becomes less and less important; by 2040 or so, it won't really matter at all.

Unfortunately I wasn't able to find any updates to this research since 2014, and the National Grid's very fancy carbon intensity API doesn't account for marginal emissions at all. But there is some other related research: