I'm trying to fabricate parts to mate an electric motor to a manual car transmission (although, I think this is a more general question).

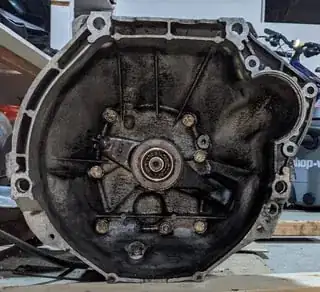

I need to connect this:

To this:

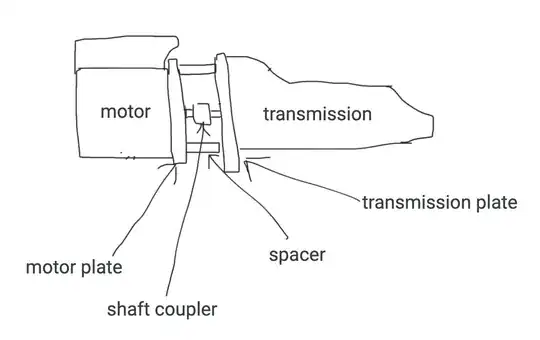

Like this:

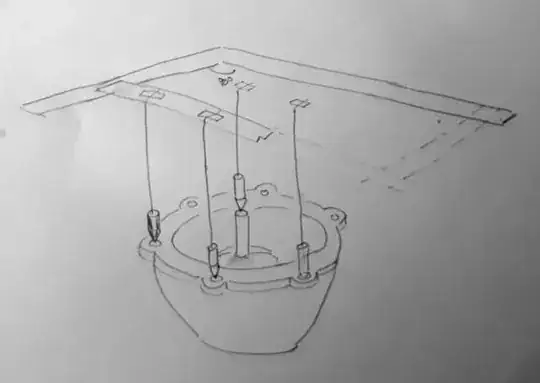

The approach I'm considering is to fabricate two metal plates: one attached to the transmission and the other to the motor, with some bolts/spacers between them, sort of like this:

In order to do this, I need to measure the existing parts accurately--specifically I want to find the X/Y positions of the bolt holes and the output/input shafts. The most important thing is that, with everything assembled, the rotating shafts line up precisely, so I need to ensure the holes on the plates properly align with each other.

However, this has been challenging. The parts are large and heavy, have complex 3d shapes, and are sitting on a concrete garage floor that isn't necessary flat and level.

I've tried a few techniques:

- Using a combination of calipers and a metal ruler (where the distance was larger than the caliper could reach) to measure from the closest edges of the holes to each other, or to other features, the using either Fusion 360 dimensional constraints, or a spreadsheet, to nudge things around until the dimensions are close. There seems to be enough error with my measurements, even when I thought I was being careful, that things generally don't line up well when I've done test cuts.

- Taping a large piece of graph paper to the part, then tracing around the holes (by putting a pen through the hole where possible, or by following where the paper indents into the hole from the other side), then measuring along the graph paper with a ruler. Or, where possible, scanning the graph paper on a flatbed scanner and trying to measure with programs like Gimp or Inkscape. It's hard to get the pen marks exact, especially on deep holes.

- Taking a picture with a camera, then trying to adjust the rotation and scale along each axis to correct it in a vector editing program. There is always quite a bit of distortion and I haven't been able to get anything to match, no matter how carefully I try to match the camera.

- I did try iPhone LIDAR, but it's not nearly precise enough.

I was hoping the designers of these parts snapped them to round number distances so I could make educated guesses what the actual distances are, but this does not seem to be the case.

One subquestion is what my tolerances should be. I've been assuming 0.5mm. However, my attempts thus far have been off by several millimeters, so this hasn't been a major consideration yet.

My questions:

- Are there other techniques for this sort of measurement, or perhaps things I could refine with the techniques I've already tried?

- Are there reasonable assumptions I can make about the original design that would help me compensate for measurement errors?