Heat pumps (commonly) use vapor compression cycles (the following is a short summary of a longer article in tlk-energy.de).

To understand this process, you only need the following three key physical relationships:

- A liquid that evaporates absorbs heat.

- A condensing gas releases heat.

- Evaporating/condensing temperature increases with increasing pressure.

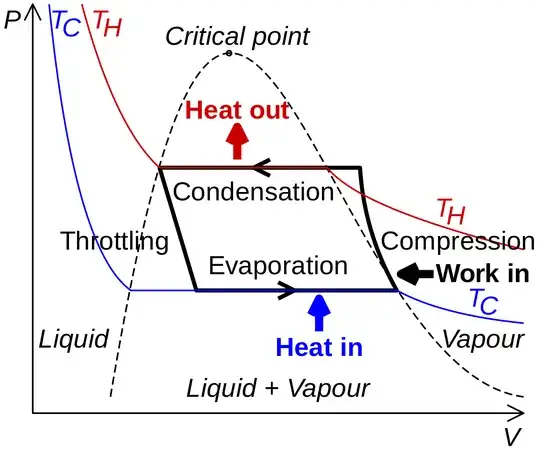

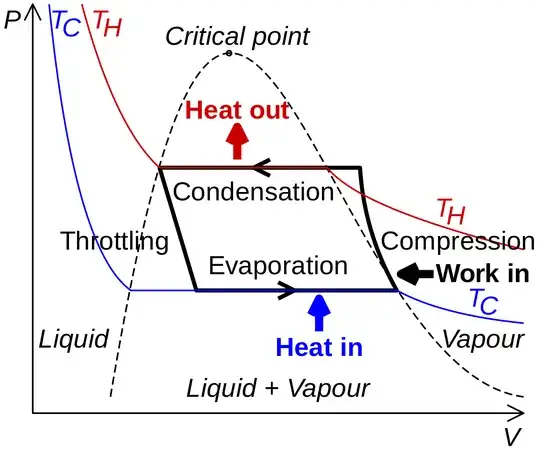

By selecting a suitable refrigerant, the following steps are repeatedly performed

- Evaporate liquid at low pressure and temperature. (Evaporator)

- Bring the resulting vapor to a higher pressure level. (Refrigerant compressor)

- Condensate refrigerant vapor at high pressure and temperature. (Condenser)

- Return the produced liquid to the low-pressure level. (Expansion)

Figure: PV diagram of the refrigerant cycle (source: Wikipedia)

The end result is that the heat energy is taken from a warmer environment and is pushed against the flow to a cooler environment. Because this process is not natural, mechanical work needs to be added during the second step (in the refrigerant compressor).

Putting the process in words

Assuming $T_{ce}$ is the cold room temperature and $T_{he}$ is the hot room temperature, then:

Starting with the evaporation step (1), the refrigerant starts with a temperature lower than $T_{ce}$, so it is able to collect heat from the cold room (at the end of the evaporation the temperature is higher but always less than $T_{ce}$); the pressure in this stage is very low.

Then the refrigerant moves into the compressor (2). In this stage, the pressure of the refrigerant is increased (almost adiabatically), and eventually, its temperature also increases and becomes greater that $T_{he}$. Usually, the refrigerant is still in gaseous form (so that the phase change is utilized).

Then at step (3), because the refrigerant's temperature is greater than $T_{he}$, it exchanges heat with the cold room. Usually, at this stage, the refrigerant from the gas turns into liquid.

Finally, in the 4th step, the pressure is lowered, so that it is able to start over from step one (liquid in low pressure).