It's not a simple relationship.

First let's deal with the kinetic energy of the wind passing through the rotor.

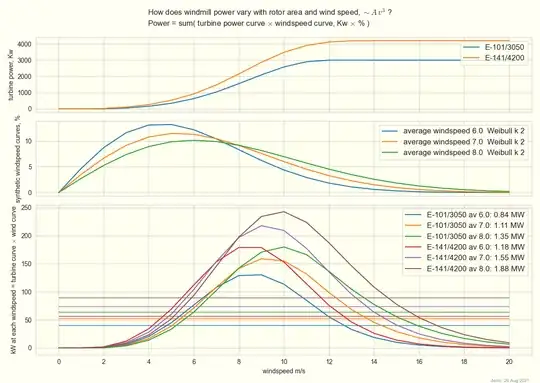

The mass of air passing through it in one second, $m$, is equal to the the density of the air ($\rho$), times the surface area of the rotor (${\pi}r^2$), times the velocity of the air ($v$). i.e. ${\rho}{\pi}r^2v$.

The kinetic energy of that air is just $\frac{1}{2}mv^2$ which is $\frac{1}{2}{\rho}{\pi}r^2v^3$ in each second.

Now, an idealised wind turbine would capture as high a proportion of that energy as it possibly could: that proportion is given by the Betz limit, which is $\frac{16}{27}$.

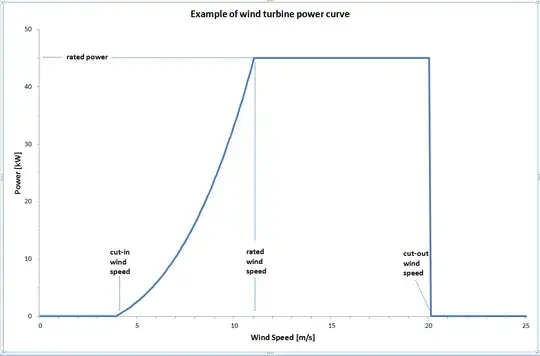

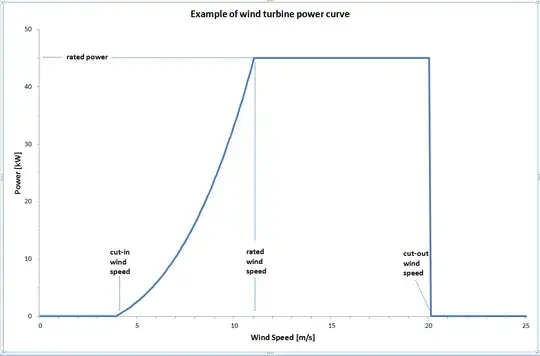

However, in the real world, we don't achieve perfection, so at best the real proportion is a bit lower than that. And also, in the real world, we have to make trade-offs based on cost. And that means that at higher speeds, which happen less often, although we could capture much more power, it's just not worth the extra expense of uprating all of the electronics and the connection to the grid, for those times, because it wouldn't represent much extra energy over the lifetime of the turbine, but would be a lot of extra cost. So the blades get feathered at higher speeds - at any speed above what we define as the rated wind speed - and the power generated is capped at the rated power. And there gets to be some rare wind speed where, in the interests of a long and healthy lifetime for the turbine, it's most economic to shut it down completely until wind speeds drop again: that's the cut-out wind speed. And at very low wind speeds, there's virtually no energy in the wind - nothing worth harvesting, and not enough to get the blades moving. So below a certain speed - the cut-in wind speed - no power is generated.

All this gives us a curve of how generated power varies with windspeed that looks like this: (source)