Without knowing additional details, my attempt at a catch-all answer:

Summary: attempt to minimize wear. Millions of cycles is a lot for even low-load contact surfaces. Use components with high hardness and smooth materials. PTFE or UHMWPE backed by metal for full-contact bearings, and AISI 52100 or AISI 440C for ball bearings. There may be an issue with contact angles at the curves.

Theory

The primary issue with millions of cycles of amply supported contacting surfaces is almost certainly going to be wear. A simple model for wear is given by the Archard equation - (Wiki), which holds that

$$

Q = k\:p\:s

$$

where $Q$ is the wear volume, $K$ is a dimensionless constant, $W$ the normal load, $L$ the sliding distance, and $H$ the hardness of the softest contacting material. The Wiki link separates hardness $H$ from $k$. The idea behind the model is that contacting surfaces don't meet uniformly, but instead at randomly distributed, microscopic height differences called asperities. As a result, the actual contact area is much smaller than the apparent macroscopic contact area, and consequently the contact loads are orders of magnitude larger than the apparent macroscopic load. Thus, the size, distribution, ductility, and hardness of the asperities plays a role, as do lubrication, mean height difference (i.e. smoothness), and the presence of external detritus. The constant $k$ depends on all of these parameters, and is typically thus typically empirically determined. However, knowing the proportionality relationships is useful in making first-passes at material selection. Specifically: increasing hardness reduces asperity formation rate, reducing wear; and decreasing surface roughness decreases number of asperities, reducing wear.

Therefore to minimize wear, a smooth, hard material, with an appropriate lubricant should be used. It would also be helpful to minimize external detritus (e.g. dirt, dust) entering the system. You can possibly go either route you describe in the question, depending on the specifics of your setup. I am assuming you require motion along a specific path with minimal deviation, like a train on rails.

First-pass Material Selection

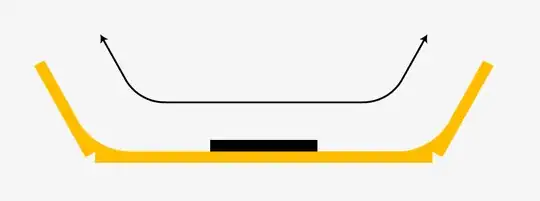

For plastic-on-plastic with no balls, it would probably help to use parts formed from a hard metal or ceramic and coated with either polyfluorocarbons (PTFE, e.g Teflon) or ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE). The trick here is that your setup requires changing direction smoothly. Getting custom made, non-linear polymer rails and bearings may be more costly than linear alternatives. Additionally, there is the problem of changing contact angles: the bearings would have to be shaped like the inner surface of a toroid, or like a saddle. If using a more typical cylindrical bearing, when the bearing meets the curve, only the leading and trailing edges will be in contact, which will cause damage.

For ball-bearings, there would need to be a special track that solves the issues of leading/trailing edge contact. Ball bearings may be made of metal or ceramic, though ceramics like silicon nitride ($\textrm{Si}_{3} \textrm{N}_{4}$) may be overkill for a low-temperature application as they are more expensive than their metal counterparts. Typically chrome steel (usually near AISI 52100) or stainless steel (usually near AISI 440C) are used as they readily form martensite (a hard, metastable steel phase) during processing and can thus be made quite hard and wear resistant.

If the weight truly is so low, adding any bearings at all will dramatically increase the weight. Instead of having bearings, is it possible to shape the panel to fit into a suitable-width groove dug into the track surface? Then make both out of teflon or UHMWPE, and back the track with brass or steel. A thin layer of dense lubricant could even make the panel float slightly, which would reduce wear to virtually zero.

If the edges are in contact, as noted in the comments, then a track could still work, but would require rounded panel contact edges. The lubricant "float trick" would be messy and probably wouldn't cause flotation when rounding corners.