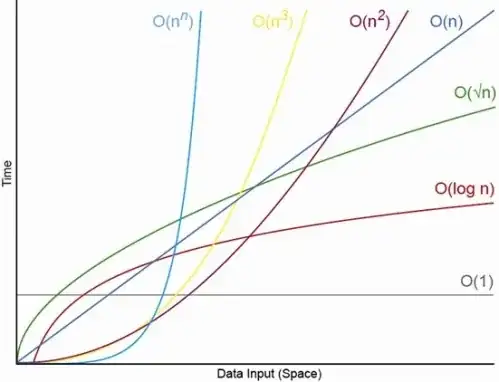

Yes, for suitably small N. There will always be a N, above which you will always have the ordering O(1) < O(lg N) < O(N) < O(N log N) < O(N^c) < O(c^N) (where O(1) < O(lg N) means that at an O(1) algorithm will take fewer operations when N is suitably large and c is a some fixed constant that is greater than 1).

Say a particular O(1) algorithm takes exactly f(N) = 10^100 (a googol) operations and an O(N) algorithm takes exactly g(N) = 2 N + 5 operations. The O(N) algorithm will give greater performance until you N is roughly a googol (actually when N > (10^100 - 5)/2), so if you only expected N to be in the range of 1000 to a billion you would suffer a major penalty using the O(1) algorithm.

Or for a realistic comparison, say you are multiplying n-digit numbers together. The Karatsuba algorithm is at most 3 n^(lg 3) operations (that is roughly O(n^1.585) ) while the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm is O(N log N log log N) which is a faster order, but to quote wikipedia:

In practice the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm starts to outperform

older methods such as Karatsuba and Toom–Cook multiplication for

numbers beyond 2^2^15 to 2^2^17 (10,000 to 40,000 decimal

digits).[4][5][6]

So if you are multiplying 500 digit numbers together, it doesn't make sense to use the algorithm that's "faster" by big O arguments.

EDIT: You can find determine f(N) compared g(N), by taking the limit N->infinity of f(N)/g(N). If the limit is 0 then f(N) < g(N), if the limit is infinity then f(N) > g(N), and if the limit is some other constant then f(N) ~ g(N) in terms of big O notation.