I'm designing an object dependency graph of my program and one ambiguity between design variants appears from time to time.

Imagine two objects having a reference to each other. Obviously, at least one reference should be assigned after object's initialization (for example, through a subscription method) and another one optionally can be a direct dependency.

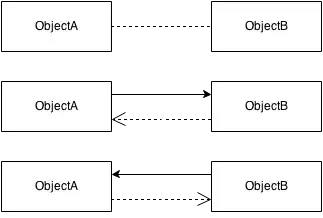

Here's an object diagram

I'm not sure I've used correct UML, so here's my description:

1) Both objects have subscription/binding methods. Usage:

A a = new A();

B b = new B();

a.Set(b);

b.Set(a);

2) ObjectB is a component of ObjectA:

A a = new A(new B());

// somewhere, possibly in a's method :

b.Set(a);

3) Third is actually an opposite of the second, no need to explain.

In my situation I can use any of these and my program will work, but I want some theoretical reasons. Can they be found?