Why is x < y < z not commonly available in programming languages?

In this answer I conclude that

- although this construct is trivial to implement in a language's grammar and creates value for language users,

- the primary reasons that this does not exist in most languages is due to its importance relative to other features and the unwillingness of the languages' governing bodies to either

- upset users with potentially breaking changes

- to move to implement the feature (i.e.: laziness).

Introduction

I can speak from a Pythonist's perspective on this question. I am a user of a language with this feature and I like to study the implementation details of the language. Beyond this, I am somewhat familiar with the process of changing languages like C and C++ (the ISO standard is governed by committee and versioned by year.) and I have watched both Ruby and Python implement breaking changes.

Python's documentation and implementation

From the docs/grammar, we see that we can chain any number of expressions with comparison operators:

comparison ::= or_expr ( comp_operator or_expr )*

comp_operator ::= "<" | ">" | "==" | ">=" | "<=" | "!="

| "is" ["not"] | ["not"] "in"

and the documentation further states:

Comparisons can be chained arbitrarily, e.g., x < y <= z is equivalent to x < y and y <= z, except that y is evaluated only once (but in both cases z is not evaluated at all when x < y is found to be false).

Logical Equivalence

So

result = (x < y <= z)

is logically equivalent in terms of evaluation of x, y, and z, with the exception that y is evaluated twice:

x_lessthan_y = (x < y)

if x_lessthan_y: # z is evaluated contingent on x < y being True

y_lessthan_z = (y <= z)

result = y_lessthan_z

else:

result = x_lessthan_y

Again, the difference is that y is evaluated only one time with (x < y <= z).

(Note, the parentheses are completely unnecessary and redundant, but I used them for the benefit of those coming from other languages, and the above code is quite legal Python.)

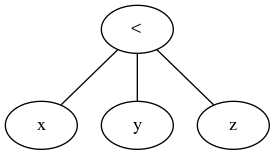

Inspecting the parsed Abstract Syntax Tree

We can inspect how Python parses chained comparison operators:

>>> import ast

>>> node_obj = ast.parse('"foo" < "bar" <= "baz"')

>>> ast.dump(node_obj)

"Module(body=[Expr(value=Compare(left=Str(s='foo'), ops=[Lt(), LtE()],

comparators=[Str(s='bar'), Str(s='baz')]))])"

So we can see that this really isn't difficult for Python or any other language to parse.

>>> ast.dump(node_obj, annotate_fields=False)

"Module([Expr(Compare(Str('foo'), [Lt(), LtE()], [Str('bar'), Str('baz')]))])"

>>> ast.dump(ast.parse("'foo' < 'bar' <= 'baz' >= 'quux'"), annotate_fields=False)

"Module([Expr(Compare(Str('foo'), [Lt(), LtE(), GtE()], [Str('bar'), Str('baz'), Str('quux')]))])"

And contrary to the currently accepted answer, the ternary operation is a generic comparison operation, that takes the first expression, an iterable of specific comparisons and an iterable of expression nodes to evaluate as necessary. Simple.

Conclusion on Python

I personally find the range semantics to be quite elegant, and most Python professionals I know would encourage the usage of the feature, instead of considering it damaging - the semantics are quite clearly stated in the well-reputed documentation (as noted above).

Note that code is read much more than it is written. Changes that improve the readability of code should be embraced, not discounted by raising generic specters of Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt.

So why is x < y < z not commonly available in programming languages?

I think there are a confluence of reasons that center around the relative importance of the feature and the relative momentum/inertia of change allowed by the governors of the languages.

Similar questions can be asked about other more important language features

Why isn't multiple inheritance available in Java or C#? There is no good answer here to either question. Perhaps the developers were too lazy, as Bob Martin alleges, and the reasons given are merely excuses. And multiple inheritance is a pretty big topic in computer science. It is certainly more important than operator chaining.

To quote James Gosling, who gives no further explanation:

JAVA omits many rarely used, poorly understood, confusing features of C++ that in our experience bring more grief than benefit. This primarily consists of operator overloading (although it does have method overloading), multiple inheritance, and extensive automatic coercions.

And these words attributed to Chris Brumme, after citing the amount of work to determine the right way to do it, user complexity, and difficulties in implementing:

It's not at all clear that this feature would pay for itself. It's something we are often asked about. It's something we haven't done due diligence on. But my gut tells me that, after we've done a deep examination, we'll still decide to leave the feature unimplemented.

These aren't great answers. Python has had multiple inheritance for a long time, it's well studied - it seems to me these are just implementations that need working out now. Is the conclusion right for the language? Maybe. It does limit the expressiveness of the languages, though.

Simple workarounds exist

Comparison operator chaining is elegant, but by no means as important as multiple inheritance. And just as Java and C# have interfaces as a workaround, so does every language for multiple comparisons - you simply chain the comparisons with boolean "and"s, which works easily enough.

Most languages are governed by committee

Most languages are evolving by committee (rather than having a sensible Benevolent Dictator For Life like Python has). And I speculate that this issue just hasn't seen enough support to make it out of its respective committees.

Can the languages that don't offer this feature change?

If a language allows x < y < z without the expected mathematical semantics, this would be a breaking change. If it didn't allow it in the first place, it would be almost trivial to add.

Breaking changes

Regarding the languages with breaking changes: we do update languages with breaking behavior changes - but users tend to not like this, especially users of features that may be broken. If a user is relying on the former behavior of x < y < z, they would likely loudly protest. And since most languages are governed by committee, I doubt we would get much political will to support such a change.