My suggestion is to make things as simple as possible. The more information you give to an object, the more complex it becomes, and the harder it is to keep track of it.

Let's break your program down into layers. What is there?

- The pieces. They only know what kind of piece they are, and what color they are (black or white)

- The board. It knows only about the pieces and how they're arranged.

- The game state. The game state knows about the board, and also about extraneous information such as captured pieces.

- The UI. The UI knows about the game state. It also knows about any graphics information like sprites.

The Pieces. A piece is... just a piece. It has a color, and a type (rook, king, queen, etc), but that's it. It can answer:

- What am I? (Rook, King, Queen, etc)

- Which side do I belong? (Black, White)

The Board. A board is just a 2D array where cells either do, or don't, have pieces. It can answer:

- Where are the pieces?

- Where are the empty squares?

In addition, based on the current state of the board, we can ask it to calculate:

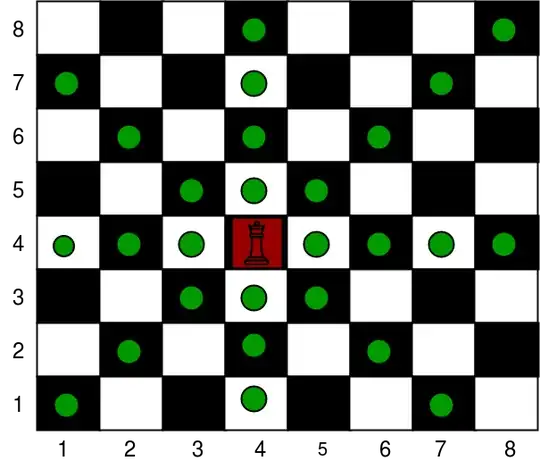

- What squares can be attacked by the piece at a particular location?

- Is a particular piece in danger?

- Is the King in Check?

- Is a proposed move legal?

Example: Take the move B3 to A4.

- If there's no piece on B3, it's illegal.

- If the piece can't move diagonally, it's illegal.

- If A4 is occupied by a piece of the same color, it's illegal.

- If the King is in Check and the move doesn't protect the King, it's illegal. And so on.

The game state. The game state keeps track of what's happened so far in the game, along with the current state of the board. This includes:

- What the board looks like now

- History of moves (Like "Queen takes B4")

- Who has captured what pieces

- Whose turn is it?

The UI. Tbe UI is responsible for drawing the game state and the board. We can ask it:

- How do things look? (What sprites or graphics primitives are used to draw a piece or the board?)

- Where should I draw stuff?

- When should I draw stuff?

The UI should be the only one that handles events. Pieces don't handle events. The game state doesn't handle events. Nor does the board handle events. When an event happens, the UI:

- Checks if whatever happened was legal

- Updates the game state if the thing was legal

- Draws the updated board (and any associated update animations)

How do I do things, like highlight possible moves? When a user mouses over the board, the UI

- Figures out which square it is

- Gets the board from the game state

- Asks the board what squares can be attacked by that piece.

This final question can be implemented in the form of a member function of the board that takes a position as input, and returns a list (or array) of positions that can be legally attacked.

Why use this approach? Every field, every property, every member that you add to class adds state. Every bit of state is something you have to manage, keep track of, and update as necessary. The code becomes a mess, and making changes is hard because one small change suddenly requires you to modify a dozen different classes.

Calculating a list of legal moves based on a 2D array of pieces is a lot cheaper than continually updating a Map<Direction, LinkedList<Cell>> for every piece. It'll be less code, too.

By breaking apart the program into layers, and giving each layer a single responsibility - to control the layer under it - we can write a program that is clean, efficent, and modular.