I re-read the question, and I think my original answer didn't address it. Here's another try.

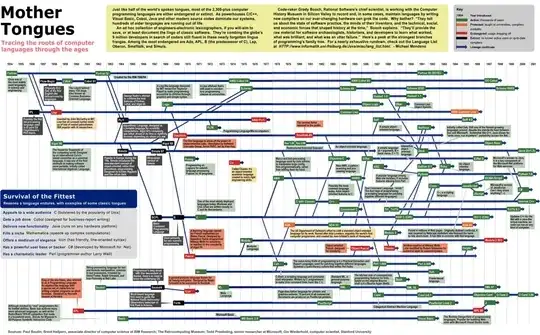

No, there has not been any serious research about programming language linguistics I'm aware of. There have been language lineages traced for two main branches and a subbranch:

For those of us with decades in the field it is obvious that programing languages have interbred, and that thus one finds most aspects of any pure paradigm in most modern programming languages, the now called multiparadigm programming languages: C#, Python, Java, .... Even previously pure functional languages like OCaml and Haskell include enough procedural (through monads) and OO features to let you do anything.

What has happened, I think, is that it became obvious that it was costly (when not silly) to have to switch programming languages just to be able to apply a the right paradigm to a given subproblem.

There remains an exception to the trend in the area of highly parallel and asynchronous systems. There the preferred languages are strictly functional, like Erlang, probably because it is easier to think about such complex systems functionally.

The non-paradigmatic part of the evolution has been on syntax. Languages that encouraged or even allowed cryptic programs have become less and less used (APL, AWK, and even Perl and LISP). The dominating syntaxes today are those of more readable (as opposed to easily writable) languages like C (C++, C#, Java, Objective-C, Scala, Go, IML, CSS, JavaScript, and also Python), Pascal (Fortran 90+x), Smalltalk (Ruby), ML/Miranda (OCaml, Haskell, Erlang), and SGML (HTML, XML).

This diagram is not completely accurate, and it is not up to date, but it gives a good idea of how much programming languages have converged since the language-per-site era of the 1970's.