Your question has the implicit assumption that at each instant each wheel is constrained to travel in a direction that is normal to its axle. For real cars traveling on real surfaces at low speeds and without significant external forces, this is mostly true -- and it simplifies the problem, so let's continue to assume that.

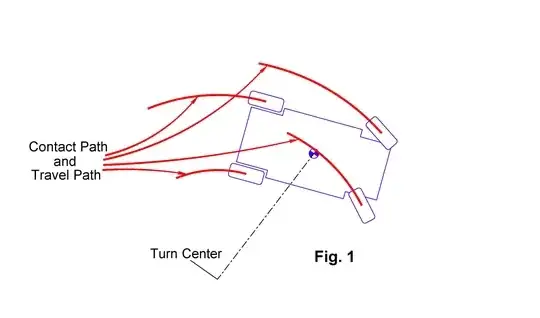

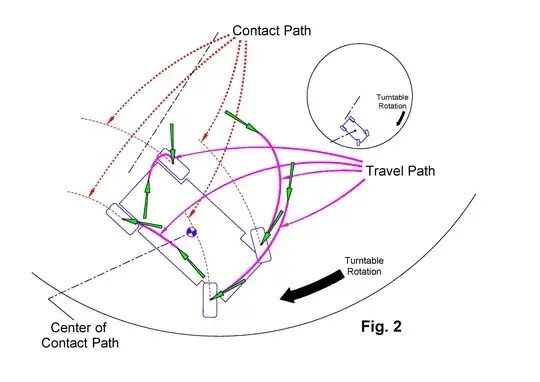

The car travels in a circle because the front wheels are turned. At any given point in its travel, for every increment in forward motion, it has to rotate by some constant multiple of that increment because the front and back wheels are not parallel. This follows from your implicit assumption about how wheels work.

If, for any given point in its path, its rotation is constant with respect to its forward motion, then it's moving in a circle (or a straight line, which is just a degenerate circle with radius = $\infty$).

So, there you are -- until you start exerting forces on it to blow it off of the track dictated by simple vehicular kinematics, it'll go in circles.